The 2D case is identified here as the waveguide with cylindrical symmetry discussed in

section 2.2.3,

so the coordinates  ,

,  and

and  stand for horizontal distance,

depth and ray slope related to the horizontal,

respectively.

The Gaussian beam expression for this case follows readily from the expression for the 2.5 case,

by taking

stand for horizontal distance,

depth and ray slope related to the horizontal,

respectively.

The Gaussian beam expression for this case follows readily from the expression for the 2.5 case,

by taking  and

and  ,

which provides the expression

,

which provides the expression

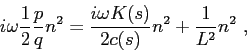

![\begin{displaymath}

P(s,n) = \frac {1}{4\pi}\sqrt{ \frac {c(s)}{c(0)} \frac {\co...

...au(s) + \frac{1}{2}\frac {p(s)}{q(s)} n^2 \right) \right] ;

\end{displaymath}](img150.png) |

(3.7) |

in this expression  and

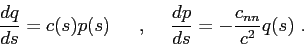

and  are related through the so-called dynamic equations:

are related through the so-called dynamic equations:

|

(3.8) |

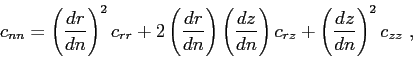

The second-order derivative along the normal can be written in terms of derivatives along  and

and  as[1]

as[1]

|

(3.9) |

where

and

Those derivatives can be identified as the components of the polarization vector

,

which in the 2D case correspond to:

,

which in the 2D case correspond to:

(see Fig.3.3).

Figure 3.3:

Polarization vectors for the 2D case.

![\includegraphics[height=80mm]{ese1}](ese1.png) |

The beam width and curvature,  and

and  , respectively[1,9],

can be calculated from

, respectively[1,9],

can be calculated from  and

and  by comparing the following expressions:

by comparing the following expressions:

which yields that

![\begin{displaymath}

K(s) = c(s) \makebox{Re}\left[ \frac {p(s)}{q(s)} \right] ,

\end{displaymath}](img163.png) |

(3.10) |

and

![\begin{displaymath}

L(s) = \sqrt{ \frac {-2}{\omega \displaystyle { \makebox{Re}\left[ \frac {p(s)}{q(s)} \right] }} } .

\end{displaymath}](img164.png) |

(3.11) |

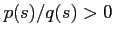

As shown by Eq.(3.11) the Gaussian beam approximation requires that  .

To this end it would be sufficient to select a non-zero real value for

.

To this end it would be sufficient to select a non-zero real value for  ,

plus the choice

,

plus the choice

,

being

,

being  a real number,

as small as possible.

Orlando Camargo Rodríguez

2012-06-21

a real number,

as small as possible.

Orlando Camargo Rodríguez

2012-06-21

![\begin{displaymath}

\mbox{$\mathbf{e}$}_s(s) =

\left[

\begin{array}{c}

\cos\th...

...ay}{r}

-\sin\theta(s) \\

\cos\theta(s)

\end{array} \right]

\end{displaymath}](img158.png)

![]() and

and ![]() , respectively[1,9],

can be calculated from

, respectively[1,9],

can be calculated from ![]() and

and ![]() by comparing the following expressions:

by comparing the following expressions: